Lecture 5: Command-line Environment

Missing Semester IAP 2020

1. Job Control

Managing and manipulating processes from the command-line.

Signals

- Unix communication mechanism for the shell

man signalfor more- When a process receives a signal it stops its execution, deals with the signal and potentially changes the flow of execution based on the information that the signal delivered (this is why signals are also known as software interrupts)

Killing a process

- In our case, when typing

Ctrl-Cthis prompts the shell to deliver aSIGINTsignal to the process - Python script that deals with a

SIGINTand continues operating anyway

#!/usr/bin/env python

import signal, time

def handler(signum, time):

print("\nI got a SIGINT, but I am not stopping")

signal.signal(signal.SIGINT, handler)

i = 0

while True:

time.sleep(.1)

print("\r{}".format(i), end="")

i += 1

- To kill this program we can now use the

SIGQUITsignal instead, by typingCtrl-\ - Here’s what happens if we send

SIGINTtwice to this program, followed bySIGQUIT. Note that^is howCtrlis displayed when typed in the terminal

$ python sigint.py

24^C

I got a SIGINT, but I am not stopping

26^C

I got a SIGINT, but I am not stopping

30^\[1] 39913 quit python sigint.py

SIGTERMis a more generic signal for asking a process to exit gracefully, and this can be sent usingkillkill -TERM <PID>

Pausing and backgrounding processes

- Signals can do other things besides killling a process

SIGSTOPpauses a process- In the terminal, typing

Ctrl-Zwill prompt the shell to send aSIGTSTPsignal, short for Terminal Stop (i.e. the terminal’s version ofSIGSTOP) - Process execution can be handled with

fgandbgfor foregrounding and backgrounding respectively jobslists the unfinished jobs associated with the current terminal session- You can refer to those jobs using their pid (you can use

pgrepto find that out) - More intuitively, you can also refer to a process using the percent symbol followed by its job number (displayed by

jobs) - To refer to the last backgrounded job you can use the

$!special parameter

- You can refer to those jobs using their pid (you can use

- One more thing to know is that the

&suffix in a command will run the command in the background, giving you the prompt back, although it will still use the shell’s STDOUT which can be annoying (use shell redirections in that case) - To background an already running program you can do

Ctrl-Zfollowed bybg - Note that backgrounded processes are still child processes of your terminal and will die if you close the terminal (this will send yet another signal,

SIGHUP) - To prevent that from happening you can run the program with

nohup(a wrapper to ignoreSIGHUP), or usedisownif the process has already been started - A special signal is

SIGKILLsince it cannot be captured by the process and it will always terminate it immediately, however, this can have bad side effects such as leaving orphaned children processes

A showcase of these concepts:

$ sleep 1000

^Z

[1] + 18653 suspended sleep 1000

$ nohup sleep 2000 &

[2] 18745

appending output to nohup.out

$ jobs

[1] + suspended sleep 1000

[2] - running nohup sleep 2000

$ bg %1

[1] - 18653 continued sleep 1000

$ jobs

[1] - running sleep 1000

[2] + running nohup sleep 2000

$ kill -STOP %1

[1] + 18653 suspended (signal) sleep 1000

$ jobs

[1] + suspended (signal) sleep 1000

[2] - running nohup sleep 2000

$ kill -SIGHUP %1

[1] + 18653 hangup sleep 1000

$ jobs

[2] + running nohup sleep 2000

$ kill -SIGHUP %2

$ jobs

[2] + running nohup sleep 2000

$ kill %2

[2] + 18745 terminated nohup sleep 2000

$ jobs

2. Terminal Multiplexers

Terminal multiplexers like tmux allow you to multiplex terminal windows using panes and tabs so you can interact with multiple shell sessions. Moreover, terminal multiplexers let you detach a current terminal session and reattach at some point later in time. This can make your workflow much better when working with remote machines since it avoids the need to use nohup and similar tricks.

Sessions

A session is an independent workspace with one or more windows.

tmuxstarts a new sessiontmux new -s NAMEstarts it with that nametmux lslists the current sessions- Within

tmuxtyping<C-b> ddetaches the current session tmux aattaches the last session. You can use-tflag to specify which

Windows

Equivalent to tabs in editors or browsers, they are visually separate parts of the same session.

<C-b> cCreates a new window. To close it you can just terminate the shells doing<C-d><C-b> NGo to the N th window. Note they are numbered<C-b> pGoes to the previous window<C-b> nGoes to the next window<C-b> ,Rename the current window<C-b> wList current windows

Panes

Like vim splits, panes let you have multiple shells in the same visual display.

<C-b> "Split the current pane horizontally<C-b> %Split the current pane vertically<C-b> <direction>Move to the pane in the specified direction. Direction here means arrow keys<C-b> zToggle zoom for the current pane<C-b> [Start scrollback. You can then press<space>to start a selection and<enter>to copy that selection<C-b> <space>Cycle through pane arrangements

Aliases

A shell alias is a short form for another command that your shell will replace automatically for you.

- To make an alias persistent you need to include it in shell startup files, like

.bashrcor.zshrc alias alias_name="command_to_alias arg1 arg2"

Example aliases:

# Make shorthands for common flags

alias ll="ls -lh"

# Save a lot of typing for common commands

alias gs="git status"

alias gc="git commit"

alias v="vim"

# Save you from mistyping

alias sl=ls

# Overwrite existing commands for better defaults

alias mv="mv -i" # -i prompts before overwrite

alias mkdir="mkdir -p" # -p make parent dirs as needed

alias df="df -h" # -h prints human readable format

# Alias can be composed

alias la="ls -A"

alias lla="la -l"

# To ignore an alias run it prepended with \

\ls

# Or disable an alias altogether with unalias

unalias la

# To get an alias definition just call it with alias

alias ll

# Will print ll='ls -lh'

3. Dotfiles

Many programs are configured using plain-text files known as dotfiles (because the file names begin with a ., e.g. ~/.vimrc, so that they are hidden in the directory listing ls by default).

Some examples of tools that can be configured through dotfiles are:

bash-~/.bashrc,~/.bash_profilegit-~/.gitconfigvim-~/.vimrcand the~/.vimfolderssh-~/.ssh/configtmux-~/.tmux.conf

Installation & Organization

How should you organize your dotfiles? They should be in their own folder, under version control, and symlinked into place using a script. This has the benefits of:

- Easy installation: if you log in to a new machine, applying your customizations will only take a minute.

- Portability: your tools will work the same way everywhere.

- Synchronization: you can update your dotfiles anywhere and keep them all in sync.

- Change tracking: you’re probably going to be maintaining your dotfiles for your entire programming career, and version history is nice to have for long-lived projects.

Portability

A common pain with dotfiles is that the configurations might not work when working with several machines, e.g. if they have different operating systems or shells. Sometimes you also want some configuration to be applied only in a given machine.

There are some tricks for making this easier. If the configuration file supports it, use the equivalent of if-statements to apply machine specific customizations. For example, your shell could have something like:

if [[ "$(uname)" == "Linux" ]]; then {do_something}; fi

# Check before using shell-specific features

if [[ "$SHELL" == "zsh" ]]; then {do_something}; fi

# You can also make it machine-specific

if [[ "$(hostname)" == "myServer" ]]; then {do_something}; fi

4. Remote Machines

It has become more and more common for programmers to use remote servers in their everyday work. If you need to use remote servers in order to deploy backend software or you need a server with higher computational capabilities, you will end up using a Secure Shell (SSH).

Executing Commands

An often overlooked feature of ssh is the ability to run commands directly. ssh foobar@server ls will execute ls in the home folder of foobar. It works with pipes, so ssh foobar@server ls | grep PATTERN will grep locally the remote output of ls and ls | ssh foobar@server grep PATTERN will grep remotely the local output of ls.

SSH keys

Key-based authentication exploits public-key cryptography to prove to the server that the client owns the secret private key without revealing the key. This way you do not need to reenter your password every time. Nevertheless, the private key (often ~/.ssh/id_rsa and more recently ~/.ssh/id_ed25519) is effectively your password, so treat it like so.

Key generation

To generate a pair you can run ssh-keygen.

ssh-keygen -o -a 100 -t ed25519 -f ~/.ssh/id_ed25519

You should choose a passphrase, to avoid someone who gets hold of your private key to access authorized servers.

Use ssh-agent or gpg-agent so you do not have to type your passphrase every time.

If you have ever configured pushing to GitHub using SSH keys, then you have probably done the steps outlined here and have a valid key pair already. To check if you have a passphrase and validate it you can run ssh-keygen -y -f /path/to/key.

Key based authentication

ssh will look into .ssh/authorized_keys to determine which clients it should let in. To copy a public key over you can use:

cat .ssh/id_ed25519.pub | ssh foobar@remote 'cat >> ~/.ssh/authorized_keys'

Copying files over SSH

There are many ways to copy files over ssh:

ssh+tee, the simplest is to usesshcommand execution and STDIN input by doingcat localfile | ssh remote_server tee serverfile. Recall thatteewrites the output from STDIN into a file.scpwhen copying large amounts of files/directories, the secure copyscpcommand is more convenient since it can easily recurse over paths. The syntax isscp path/to/local_file remote_host:path/to/remote_filersyncimproves uponscpby detecting identical files in local and remote, and preventing copying them again. It also provides more fine grained control over symlinks, permissions and has extra features like the--partialflag that can resume from a previously interrupted copy.rsynchas a similar syntax toscp.

Port forwarding

In many scenarios you will run into software that listens to specific ports in the machine. When this happens in your local machine you can type localhost:PORT or 127.0.0.1:PORT, but what do you do with a remote server that does not have its ports directly available through the network/internet?.

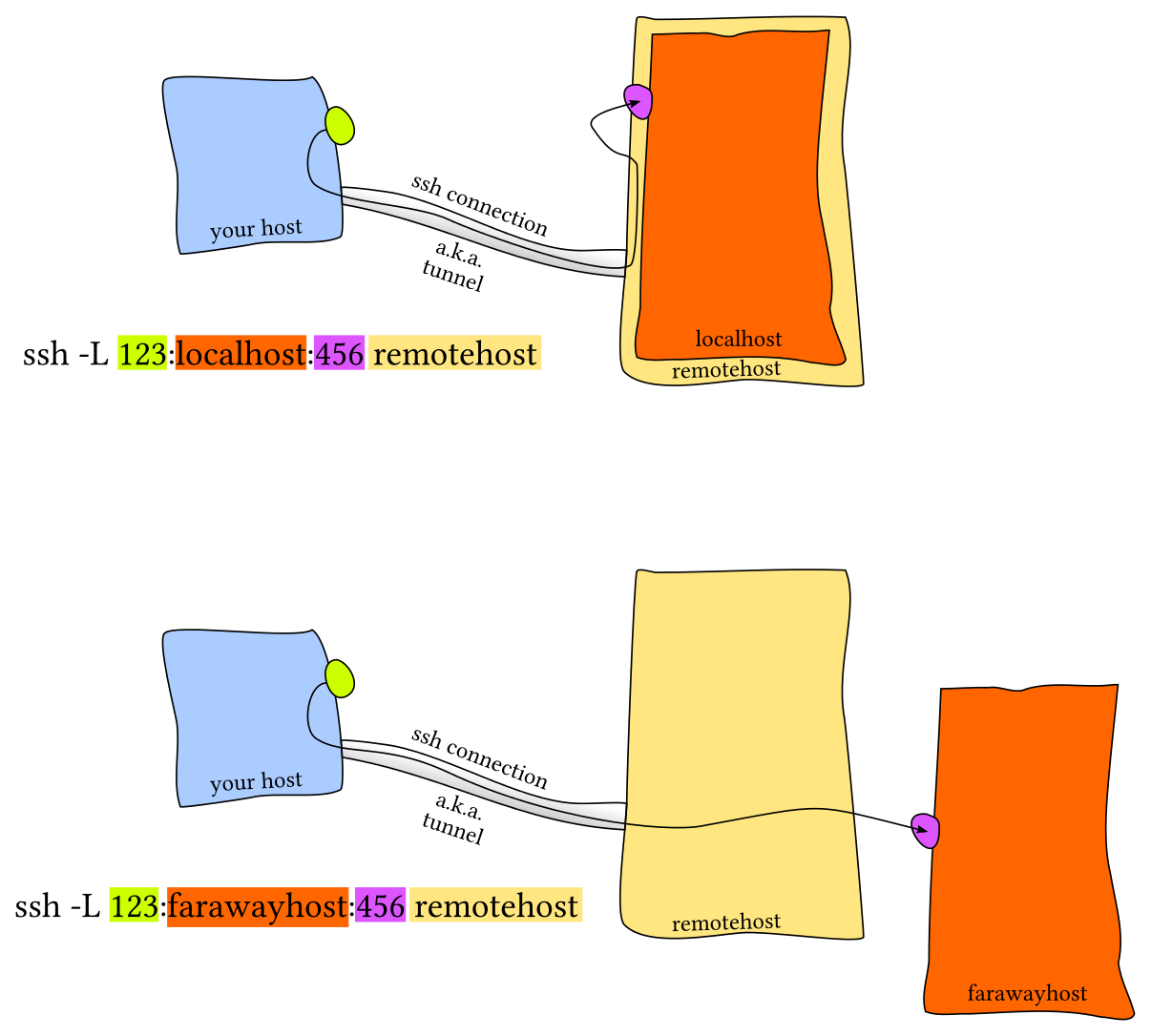

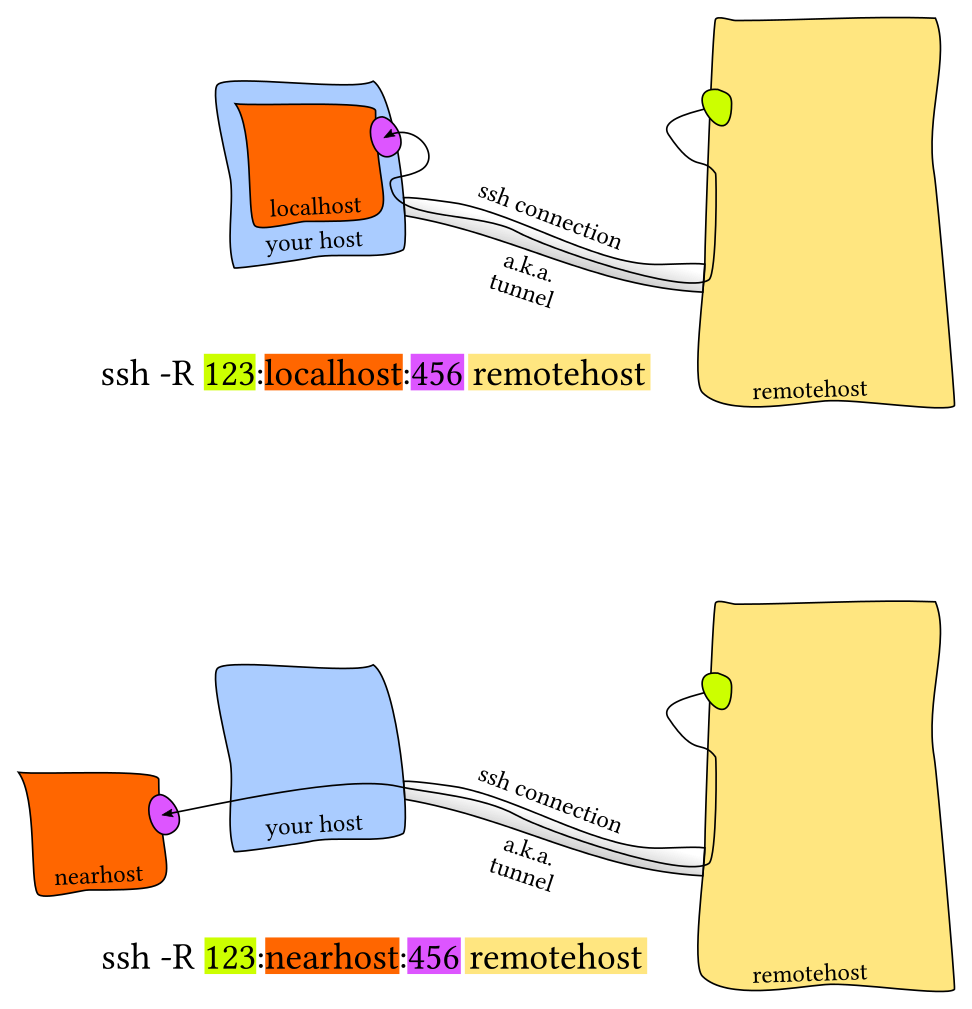

This is called port forwarding and it comes in two flavors: Local Port Forwarding and Remote Port Forwarding (see the pictures for more details, credit of the pictures from this StackOverflow post).

Local Port Forwarding:

Remote Port Forwarding:

The most common scenario is local port forwarding, where a service in the remote machine listens in a port and you want to link a port in your local machine to forward to the remote port. For example, if we execute jupyter notebook in the remote server that listens to the port 8888. Thus, to forward that to the local port 9999, we would do ssh -L 9999:localhost:8888 foobar@remote_server and then navigate to locahost:9999 in our local machine.

SSH configuration

It may seem like a good idea, but there’s a better way to shorten SSH commands besides aliases. It’s tempting, but avoid this:

alias my_server="ssh -i ~/.id_ed25519 --port 2222 -L 9999:localhost:8888 foobar@remote_server

Use ~/.ssh/config instead:

Host vm

User foobar

HostName 172.16.174.141

Port 2222

IdentityFile ~/.ssh/id_ed25519

LocalForward 9999 localhost:8888

# Configs can also take wildcards

Host *.mit.edu

User foobaz

An additional advantage of using the ~/.ssh/config file over aliases is that other programs like scp, rsync, & mosh are able to read it as well and convert the settings into the corresponding flags.

Note that the ~/.ssh/config file can be considered a dotfile, and in general it is fine for it to be included with the rest of your dotfiles. However, if you make it public, think about the information that you are potentially providing strangers on the internet: addresses of your servers, users, open ports, etc. This may facilitate some types of attacks so be thoughtful about sharing your SSH configuration.

Server side configuration is usually specified in /etc/ssh/sshd_config. Here you can make changes like disabling password authentication, changing ssh ports, enabling X11 forwarding, etc. You can specify config settings on a per user basis.

Mosh - better SSH for mobile

A common pain when connecting to a remote server are disconnections due to your computer shutting down, going to sleep, or changing networks. Moreover if one has a connection with significant lag using ssh can become quite frustrating. Mosh, the mobile shell, improves upon ssh, allowing roaming connections, intermittent connectivity and providing intelligent local echo.

Sometimes it is convenient to mount a remote folder. sshfs can mount a folder on a remote server locally, and then you can use a local editor.

Shells & Frameworks

During shell tool and scripting we covered the bash shell because it is by far the most ubiquitous shell and most systems have it as the default option. Nevertheless, it is not the only option.

For example, the zsh shell is a superset of bash and provides many convenient features out of the box such as:

- Smarter globbing,

** - Inline globbing/wildcard expansion

- Spelling correction

- Better tab completion/selection

- Path expansion (

cd /u/lo/bwill expand as/usr/local/bin)

Frameworks can improve your shell as well. Some popular general frameworks are prezto or oh-my-zsh, and smaller ones that focus on specific features such as zsh-syntax-highlighting or zsh-history-substring-search. Shells like fish include many of these user-friendly features by default. Some of these features include:

- Right prompt

- Command syntax highlighting

- History substring search

- manpage based flag completions

- Smarter autocompletion

- Prompt themes

One thing to note when using these frameworks is that they may slow down your shell, especially if the code they run is not properly optimized or it is too much code. You can always profile it and disable the features that you do not use often or value over speed.

Terminal Emulators

Along with customizing your shell, it is worth spending some time figuring out your choice of terminal emulator and its settings. There are many many terminal emulators out there (here is a comparison).

Since you might be spending hundreds to thousands of hours in your terminal it pays off to look into its settings. Some of the aspects that you may want to modify in your terminal include:

- Font choice

- Color Scheme

- Keyboard shortcuts

- Tab/Pane support

- Scrollback configuration

- Performance (some newer terminals like Alacritty or kitty offer GPU acceleration).